Processing Power: What Every Parent Needs to Know

Processing and Its Relationship to Cognition, Maturity, and Global Function

What every parent needs to understand about processing:

It’s not about chronological age, it’s processing power.

by Bob Doman

Whether your child is “typical,” has learning or attention issues or special needs, you need to understand your child’s processing level and its global significance.

Whether your child is “typical,” has learning or attention issues or special needs, you need to understand your child’s processing level and its global significance.

Knowing and understanding your child’s processing provides you with some important insights into how they take in information and learn and think much better than does their chronological age. This information provides you with vital information that can help you be proactive and help them achieve their innate potential.

The term processing power is generally reserved for and applied to computers and their ability to manipulate data and the speed with which they can do so. People understand that the more processing power their computer has, the better. What most people do not understand is the significance of human processing and its relevance to child development and global human function.

At NACD we have been working with the development of human processing power and have developed software and hundreds of activities to assist in this development for more than 40 years, working with tens of thousands of children and adults.

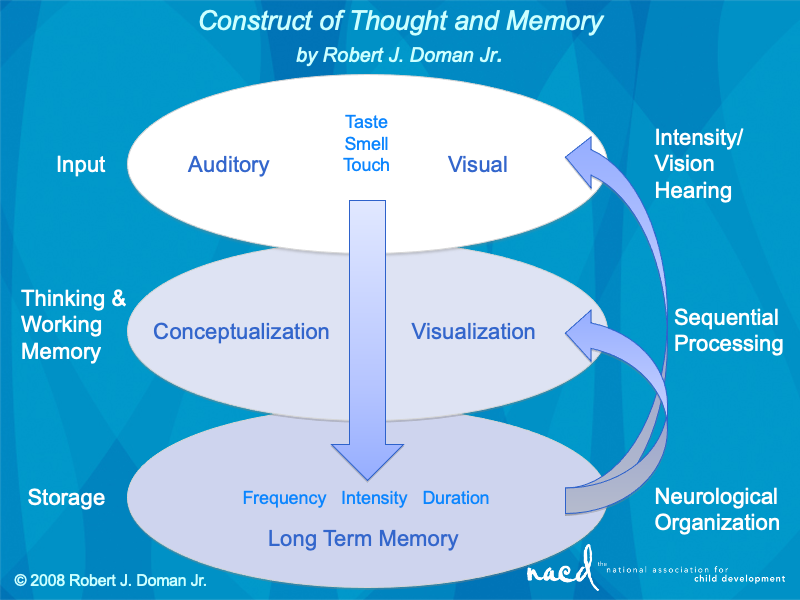

We view human processing as the ability to take in and to manipulate visual and auditory information, to learn and manipulate information, and to think. These functions are also the neurological pieces that underlie our maturity and behavior and which in turn provide us with the means to develop the mental ability to do such things as plan, prioritize, develop self-control, organize, and more–cognitive function.

The more associated pieces of information we can process, the more we take in of what there is to see and hear, the more we learn, and the higher our level of cognition. What different individuals process varies significantly, as does their perception of the world and their ability to think and function. None of us see, hear, or process the world the same way or think alike; but the stronger our processing power, the better equipped we are to learn and think, understand our world, and function in it.

Processing power develops in children. It changes, and what changes can be developed at any point in our lives.

Neuroplasticity is the mechanism by which the brain develops and changes. Everything we put into our brains and everything we think, feel, and use our brains for to some degree physically changes our brains and its function for better or worse. Our processing power impacts the quality and quantity of data we take in and our ability to manipulate and think.

The more we learn and know, the more meaning and significance what we perceive has, which in turn affects the relevance to our brains, and thus in turn affects what we take in and process. The world that is perceived is the world as seen and heard through our ability to process it and its relative significance. And the more of those pieces we can manipulate together, the greater our complexity of thought and ability to think.

Psychologists use the terms short-term memory, working memory, and executive function, rather than processing power, but processing power really says it better. The term “memory” doesn’t really describe, and to some degree distorts and minimizes, the neurological mechanism and significance of our processing power.

When we first start working with a child, and at NACD that means the whole child, we begin with basic functions, which include simply their ability to see, hear, feel, taste, and smell. These are things that are often taken for granted. In some cases, there are specific factors affecting these functions, ranging from actual injuries to the brain, to genetics, to more common problems such as middle ear fluid, degrees of hearing loss, to a wide variety of issues affecting vision, etc. But the reality is that all of these sensory functions need to develop or be developed in every child because they affect the child’s ability to process input, process the world. The brain needs to learn how to process and interpret this sensory information. If the child cannot perceive this sensory information, they need to be provided with the means with which to develop these functions or, to use another computer term, garbage in-garbage out. You first must see, hear, feel, taste, and smell properly. Most children on the autism spectrum, and to varying degrees children with other developmental problems, have issues that negatively impact the brain’s ability to learn how to process even basic sensory information appropriately. These sensory issues need to be addressed in order to develop processing power and further overall development.

Measuring Processing Power

Processing power can be gauged by looking at auditory and visual sequential processing.

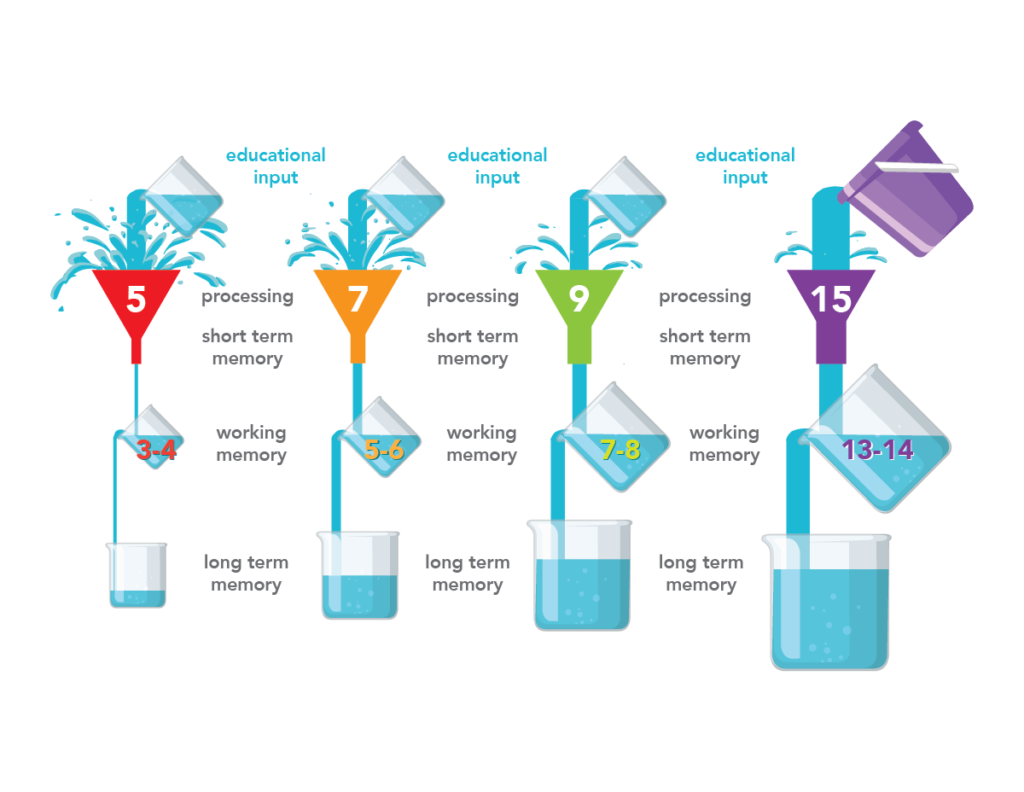

For most children and adults functioning above the level of the average five-year-old, sequential processing can be tested by measuring what is referred to as a digit span. To test someone’s auditory digit span (the measure of how much the individual takes in from what they hear), you would simply say a sequence of numbers slowly (1 second intervals) in a monotone voice and have them repeat the sequence. Do not repeat the sequence if they miss it; give a different sequence of numbers. Start with 3 random numbers (using numbers from 0-9, do not repeat a number until you have surpassed a sequence of ten numbers), and give longer sequences until they can no longer repeat the sequence. The highest sequence they can get correct is their auditory digit span.

Following the same method, you can also test their reverse auditory digit span, presenting the numbers in the same way, but asking the participant to repeat the numbers backwards. The highest number of digits they can repeat backwards is their reverse auditory digit span.

Likewise, you can also test the visual digit span. Following a similar procedure, clearly write a series of large font numbers starting with a sequence of three numbers on a card or whiteboard; then show the participant the sequence and have them immediately read it aloud, without letting them review it. Immediately remove the card and have them repeat the sequence. As with the auditory test, continue until they can no longer repeat the sequence. Repeat this process again, but after having read the sequence from left to right, ask them to repeat the sequence backwards to ascertain their reverse visual digit span.

Some children younger than five who are familiar with numbers and can identify them easily can be tested with digit spans. Children can be tested prior to this by asking them to repeat a series of names of familiar objects, such as “spoon, table, ball” for auditory sequencing, or visually showing them a sequence of pictures and having them name them as you point to them and then removing them and having the child name the objects in order. Some children will be able to understand (“process”) a reverse sequence when they can do a forward sequence of 4; but many will not be able to until they can do a sequence of 5 digits forward.

Younger children can be crudely tested by having them follow a sequence of directions such as “Touch nose, ear,” or asking them to find this and that.

Forward digit spans are generally referred to as a representation of short-term memory, and reverse digit spans as a representation of working memory. But for now simply see these numbers as a representation of processing power.

At NACD we have tested the processing power of tens of thousands of individuals, and in some cases tested and followed some individuals for decades. Digit spans themselves are used as a testable number, but the primary processing power gauge is the individual’s actual function– their ability to understand and use language, their problem solving, behavior, and maturity. For younger children there are some very direct correlations between functions such as language and behavior and sequential processing.

When most children are in the processing range of 1-2 (with typical children this generally correlates with being 8 months to 24 months of age), they are relatively easy to please, generally happy unless they have a basic need such as being hungry, needing to sleep, or needing a diaper change. At this level of processing power the first random words begin popping out. As the child moves to stronger 2s, the behavior tends to begin to get more difficult and we often get tantrums–terrible two behaviors–but the child also starts using meaningful words and 2-word combinations. As we work into sequential processing power of 3, we start seeing what we refer to as “lock and block” behavior, which means that if the child perceives a request as something fun, typical, and nonthreatening, they will comply; but asking them to do something that is atypical or that they sense as strange or threatening in some way will often result in them just staring at you and refusing to comply. Behavior is to a significant degree a reflection of the child’s complexity of thought–processing power. At this stage the language moves into phrases of three to four words, and as the child moves toward processing a 4 they start using sentences and can be bargained /reasoned with. All these changes are reflections of the child’s ability to process (understand) and to think with greater and greater complexity. As processing power increases from here, so does the ability to process more and more of what is said and what is seen, and to think with greater and greater complexity. Other factors begin to figure into the equation, such as the individual’s ability to think conceptually (in words) and to visualize (think in pictures).

Processing power is what ultimately permits the individual to develop higher level mental function and associated maturity. The term “executive function” is used to describe these higher levels of function, which include things such as the ability to adapt, plan, self-regulate and control, time management, and organization. These functions only exist to the degree that our processing power permits.

To understand any child and many adults it’s not about chronological age, it’s Processing Power.

Whether we are trying to understand a special needs child, a “typical” child, or even an adult for that matter, one of our best insights as to how they function and thus what we should expect from them and what to do to help them improve is understanding their processing power. The degree to which we can identify their level of function, the greater our ability to target their needs.

The sad reality is that most educators have no idea as to a child’s processing ability and thus have limited ways at best to appropriately target their needs. For example, a special education teacher and an occupational therapist may be trying to get a six-year-old child with Down syndrome to write or cut with scissors with very minimal or no success because the six-year-old child has the processing power of a typical 2-year-old. Would you work hard to get a two-year-old to write or use scissors? Not if you had any sense. There are a lot of much more appropriate things to be teaching a child at this level, not the least of which is how to process more.

If you had a typically functioning four or five-year-old, would you be surprised if compared to a much older child they had a short attention span, were a bit distractible, and were still immature? No! Now if you had an eight, nine, or ten-year-old child, or even older, who had a short attention span and was distractible and immature, would you just jump to the conclusion that they had ADHD? Sadly, this is the label that is given to most of these children, even though they still have the processing power of a four or five-year-old and their attention span, distractibility, and maturity are in fact appropriate for where their processing is. Solution: raise their processing power! If you had a four-year-old whom you wanted to sit and attend in a third or fourth grade classroom, how would you do that? You would probably have to drug them. Would you do that, or would you wait until they were older and had developed the processing power needed?

What about the sixteen-year-old who is struggling in school, can’t get himself out of bed in the morning, is irresponsible, socially inept, and who wants to get a driver’s license? If you were to test his processing and were to discover that he had all these issues because he had the processing power of a five-year-old, would you want him to have a driver’s license? Do him and the world a favor and don’t put him behind the wheel of a car until you’ve raised his processing power to the point that he could develop some real executive function and make good decisions.

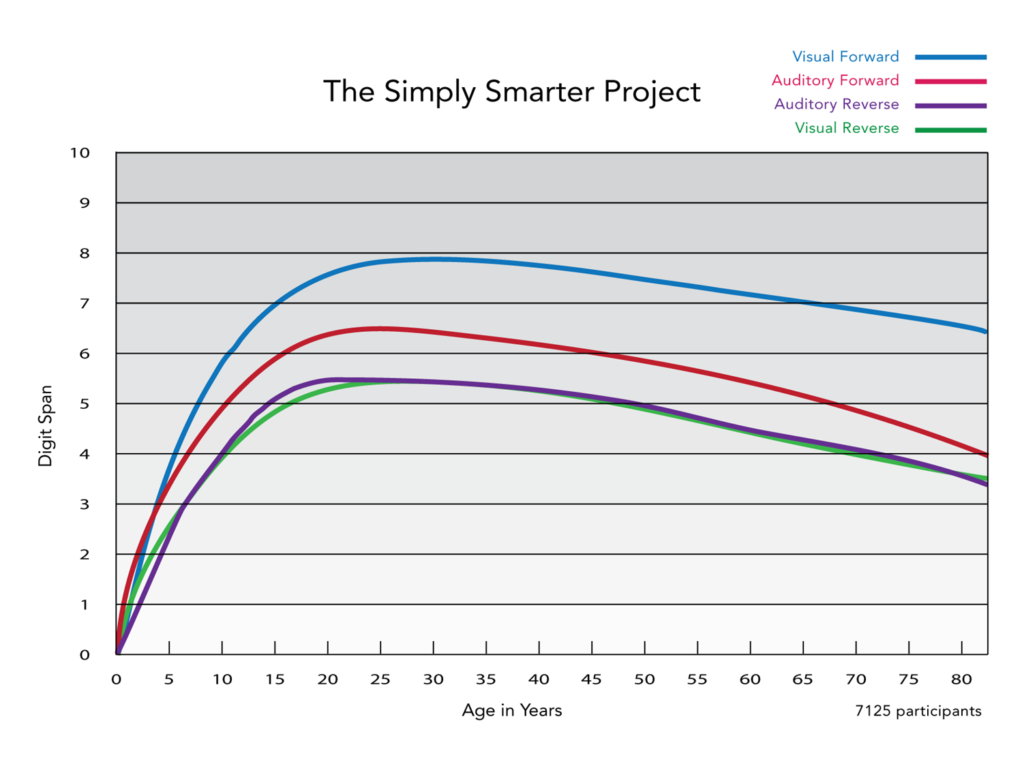

Typically, processing develops rapidly from infancy to about nine years of age, (see https://www.nacd.org/short-term-and-working-memory-clinical-insights) and then very slowly develops a bit from nine years until into the twenties. After the twenties, without intervention of some form, or exceptional use and demands, it starts a slow decline. Sadly, the processing level of most seven-year-olds is close to most young adults.

If you look at the change in global development between an infant and an average seven-year-old, it is quite spectacular. That tremendous change is not due to the child getting older; it’s due to the opportunities they have received and the resulting increase in their processing power. If you see children with high global function, you are generally looking at a child with superior processing. There does not appear to be any limit as to how far processing can develop given the targeted input to do it.

What develops changes, what changes can be developed.

Until the educators and psychologists and particularly the academics understand that the foundational pieces that permit us all to function can be developed, very few will ever come close to achieving their innate potential.

It’s a tragedy that our potential as individuals and as a world population remain untapped and that children and adults are labeled and denied the opportunity to achieve their innate potential. “Typical” or “average” is not a reflection of the potential anyone was born with, it’s a reflection of limited opportunity. We can all do better and function at higher levels if given the opportunity.

Developing processing power is something that should be an integral part of every child’s day.

Parents need to educate themselves, become active participants, and become the force that helps their children become all that they can be.

Related Apps/Software

NACD has developed many activities to develop processing power. Programs that are accessible to the general public include:

Simply Smarter

Cognition Coach – Toddlers

Cognition Coach – Preschool

Related Graphs

The Simply Smarter Project

Construct of Thought and Memory

Reprinted by permission of The NACD Foundation, Volume 35 No.1, 2022 ©NACD

Related Articles

https://www.nacd.org/the-effect-of-the-simply-smarter-program-on-short-term-memory-working-m

https://www.nacd.org/nacdwasatch-peak-academy-school-model-program/